How Did Louis Daguerre Contribution to Photography

| Louis Daguerre | |

|---|---|

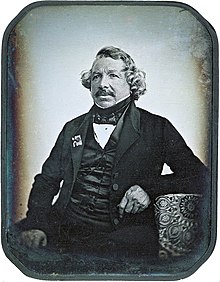

Daguerre around 1844 | |

| Born | Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-11-18)18 November 1787 Cormeilles-en-Parisis, French republic |

| Died | 10 July 1851(1851-07-10) (aged 63) Bry-sur-Marne, France |

| Known for | Invention of the daguerreotype process |

| Signature | |

| |

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre ( də-GAIR , French: [lwi ʒɑk mɑ̃de daɡɛʁ]; 18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851) was a French creative person and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as i of the fathers of photography. Though he is virtually famous for his contributions to photography, he was also an achieved painter, scenic designer, and a developer of the diorama theatre.

Biography [edit]

Louis Daguerre was born in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val-d'Oise, France. He was apprenticed in architecture, theatre design, and panoramic painting to Pierre Prévost, the first French panorama painter. Exceedingly adept at his skill of theatrical illusion, he became a celebrated designer for the theatre, and after came to invent the diorama, which opened in Paris in July 1822.

In 1829, Daguerre partnered with Nicéphore Niépce, an inventor who had produced the world'south first heliograph in 1822 and the oldest surviving camera photo in 1826 or 1827.[1] [ii] Niépce died suddenly in 1833, only Daguerre continued experimenting, and evolved the process which would subsequently be known as the daguerreotype. After efforts to interest private investors proved fruitless, Daguerre went public with his invention in 1839. At a joint coming together of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Arts on 7 Jan of that year, the invention was appear and described in general terms, but all specific details were withheld. Under assurances of strict confidentiality, Daguerre explained and demonstrated the process simply to the Academy's perpetual secretary François Arago, who proved to be an invaluable advocate.[three] Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre'south studio. The images were enthusiastically praised as almost miraculous, and news of the daguerreotype quickly spread. Arrangements were fabricated for Daguerre's rights to be acquired by the French Government in exchange for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce's son Isidore; then, on xix August 1839, the French Regime presented the invention every bit a souvenir from France "free to the earth", and consummate working instructions were published. In 1839, he was elected to the National Academy of Pattern equally an Honorary Academician.

Daguerre died, from a centre attack,[4] on 10 July 1851 in Bry-sur-Marne, 12 km (7 mi) from Paris. A monument marks his grave at that place.

Daguerre'due south name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel tower.

Development of the daguerreotype [edit]

An engraving of Daguerre during his career

In the mid-1820s, prior to his association with Daguerre, Niépce used a blanket of bitumen of Judea to brand the kickoff permanent photographic camera photographs. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to calorie-free and the unhardened portion was and so removed with a solvent. A camera exposure lasting for hours or days was required. Niépce and Daguerre afterward refined this process, but unacceptably long exposures were still needed.

After the death of Niépce in 1833, Daguerre concentrated his attending on the calorie-free-sensitive properties of silver salts, which had previously been demonstrated by Johann Heinrich Schultz and others. For the process which was somewhen named the daguerreotype, he exposed a thin silvery-plated copper canvas to the vapour given off past iodine crystals, producing a blanket of light-sensitive silver iodide on the surface. The plate was then exposed in the photographic camera. Initially, this process, besides, required a very long exposure to produce a distinct image, but Daguerre made the crucial discovery that an invisibly faint "latent" prototype created by a much shorter exposure could be chemically "developed" into a visible image. Upon seeing the image, the contents of which are unknown, Daguerre said, "I have seized the light – I have arrested its flying!"[five]

View of the Boulevard du Temple, taken past Daguerre in 1838 in Paris, includes the earliest known photograph of a person. The image shows a busy street, but because the exposure had to go along for four to five minutes the moving traffic is not visible. At the lower right, withal, a human patently having his boots polished, and the bootblack polishing them, were motionless enough for their images to be captured. At that place is also what appears to be a young girl looking out of a window at the photographic camera.

The latent epitome on a daguerreotype plate was developed past subjecting it to the vapour given off past mercury heated to 75 °C. The resulting visible image was so "fixed" (made insensitive to further exposure to low-cal) by removing the unaffected silver iodide with full-bodied and heated common salt water. After, a solution of the more than effective "hypo" (hyposulphite of soda, now known as sodium thiosulfate) was used instead.[6]

The resultant plate produced an exact reproduction of the scene. The image was laterally reversed—as images in mirrors are—unless a mirror or inverting prism was used during exposure to flip the image. To be seen optimally, the epitome had to be lit at a certain bending and viewed and so that the smooth parts of its mirror-similar surface, which represented the darkest parts of the image, reflected something dark or dimly lit. The surface was subject to tarnishing past prolonged exposure to the air and was then soft that information technology could exist marred by the slightest friction, so a daguerreotype was almost always sealed under drinking glass before beingness framed (equally was commonly done in France) or mounted in a small folding case (every bit was normal in the UK and United states).

Daguerreotypes were usually portraits; the rarer mural views and other unusual subjects are now much sought-after past collectors and sell for much higher prices than ordinary portraits. At the time of its introduction, the process required exposures lasting ten minutes or more for brightly sunlit subjects, so portraiture was an impractical ordeal. Samuel Morse was astonished to learn that daguerreotypes of the streets of Paris did not prove whatsoever people, horses or vehicles, until he realized that due to the long exposure times all moving objects became invisible. Inside a few years, exposures had been reduced to as piddling every bit a few seconds by the use of additional sensitizing chemicals and "faster" lenses such as Petzval's portrait lens, the outset mathematically calculated lens.

The daguerreotype was the Polaroid motion picture of its day: it produced a unique paradigm which could only be duplicated by using a camera to photo the original. Despite this drawback, millions of daguerreotypes were produced. The paper-based calotype process, introduced by Henry Trick Talbot in 1841, allowed the product of an unlimited number of copies by simple contact printing, but it had its own shortcomings—the grain of the paper was obtrusively visible in the paradigm, and the extremely fine detail of which the daguerreotype was capable was non possible. The introduction of the moisture collodion process in the early 1850s provided the basis for a negative-positive print-making process not subject to these limitations, although information technology, like the daguerreotype, was initially used to produce one-of-a-kind images—ambrotypes on glass and tintypes on black-lacquered iron sheets—rather than prints on paper. These new types of images were much less expensive than daguerreotypes, and they were easier to view. By 1860 few photographers were still using Daguerre'due south procedure.

The same small ornate cases commonly used to house daguerreotypes were also used for images produced past the later and very different ambrotype and tintype processes, and the images originally in them were sometimes later discarded then that they could be used to display photographic paper prints. It is now a very common error for any image in such a case to be described equally "a daguerreotype". A true daguerreotype is always an image on a highly polished silver surface, ordinarily under protective drinking glass. If it is viewed while a brightly lit sail of white paper is held so as to be seen reflected in its mirror-like metal surface, the daguerreotype prototype will appear as a relatively faint negative—its dark and light areas reversed—instead of a normal positive. Other types of photographic images are almost never on polished metallic and practise not exhibit this peculiar characteristic of appearing positive or negative depending on the lighting and reflections.

Competition with Talbot [edit]

Unbeknownst to either inventor, Daguerre's developmental work in the mid-1830s coincided with photographic experiments being conducted by William Henry Pull a fast one on Talbot in England. Talbot had succeeded in producing a "sensitive paper" impregnated with silver chloride and capturing modest camera images on it in the summer of 1835, though he did not publicly reveal this until January 1839. Talbot was unaware that Daguerre's tardily partner Niépce had obtained similar small camera images on silvery-chloride-coated newspaper nearly twenty years earlier. Niépce could observe no way to keep them from darkening all over when exposed to lite for viewing and had therefore turned away from silver salts to experiment with other substances such as bitumen. Talbot chemically stabilized his images to withstand subsequent inspection in daylight by treating them with a potent solution of mutual salt.

When the first reports of the French University of Sciences announcement of Daguerre's invention reached Talbot, with no details well-nigh the exact nature of the images or the process itself, he assumed that methods similar to his own must have been used, and promptly wrote an open up letter to the Academy challenge priority of invention. Although it presently became apparent that Daguerre's procedure was very unlike his ain, Talbot had been stimulated to resume his long-discontinued photographic experiments. The developed out daguerreotype process only required an exposure sufficient to create a very faint or completely invisible latent image which was so chemically developed to full visibility. Talbot's before "sensitive paper" (at present known as "salted paper") procedure was a printed out process that required prolonged exposure in the camera until the paradigm was fully formed, but his later on calotype (too known as talbotype) paper negative process, introduced in 1841, also used latent epitome development, greatly reducing the exposure needed, and making it competitive with the daguerreotype.

Daguerre's agent Miles Berry applied for a British patent under the instruction of Daguerre only days before France declared the invention "free to the earth". The United Kingdom was thereby uniquely denied France's gratis souvenir, and became the only country where the payment of license fees was required. This had the issue of inhibiting the spread of the procedure there, to the eventual reward of competing processes which were subsequently introduced into England. Antoine Claudet was 1 of the few people legally licensed to brand daguerreotypes in Britain.[seven]

Diorama theatres [edit]

Diagram of the London diorama building

In the bound of 1821, Daguerre partnered with Charles Marie Bouton with the common goal of creating a diorama theatre. Daguerre had expertise in lighting and breathtaking effects, and Bouton was the more experienced painter. However, Bouton eventually withdrew, and Daguerre acquired sole responsibility of the diorama theatre.

The first diorama theatre was built in Paris, adjacent to Daguerre'southward studio. The commencement exhibit opened 11 July 1822 showing two tableaux, i by Daguerre and i past Bouton. This would go a pattern. Each exhibition would typically have two tableaux, one each past Daguerre and Bouton. Also, one would be an interior delineation, and the other would be a landscape. Daguerre hoped to create a realistic illusion for an audience, and wanted audiences to be not merely entertained, only awe-stricken. The diorama theatres were magnificent in size. A big translucent canvas, measuring around 70 ft wide and 45 ft tall, was painted on both sides. These paintings were vivid and detailed pictures, and were lit from different angles. As the lights changed, the scene would transform. The audition would begin to see the painting on the other side of the screen. The outcome was awe-inspiring. "Transforming impressions, mood changes, and movements were produced past a organisation of shutters and screens that allowed light to exist projected- from behind- on alternately separate sections of an image painted on a semi-transparent backdrop" (Szalczer).

Because of their size, the screens had to remain stationary. Since the tableaux were stationary, the auditorium revolved from i scene to some other. The auditorium was a cylindrical room and had a single opening in the wall, like to a proscenium arch, through which the audition could watch a "scene". Audiences would average around 350, and most would stand, though limited seating was provided. Twenty-one diorama paintings were exhibited in the starting time eight years. These included 'Trinity Chapel in Canterbury Cathedral', 'Chartres Cathedral', 'Urban center of Rouen', and 'Environs of Paris' past Bouton; 'Valley of Sarnen', 'Harbour of Brest', 'Holyroodhouse Chapel', and 'Roslin Chapel' by Daguerre.

The Roslin Chapel was known for a few legends involving an unconsuming fire. The legend goes that the Chapel has appeared to be in flames just earlier a loftier-status expiry, just has later shown no harm from any such fire. This chapel was besides known for beingness unique in its architectural dazzler. Daguerre was aware of both of these aspects of Roslin Chapel, and this fabricated it a perfect field of study for his diorama painting. The legends connected with the chapel would exist sure to attract a large audition. Interior of Roslin Chapel in Paris opened 24 September 1824 and closed February 1825. The scene depicted low-cal coming in through a door and a window. Foliage shadows could be seen at the window, and the way the lite'due south rays shone through the leaves was scenic and seemed to "get across the power of painting" (Maggi). Then the light faded on the scene as if a cloud was passing over the sun. The Times dedicated an article to the exhibition, calling it "perfectly magical".

Diorama became a popular new medium, and imitators arose. It is estimated that profits reached as much equally 200,000 francs. This would require 80,000 visitors at an entrance fee of 2.fifty francs. Another diorama theatre opened in Regent'south Park, London, taking only four months to build. It opened in September 1823. The almost prosperous years were the early to mid-1820s.

The dioramas prospered for a few years until going into the 1830s. Then, inevitably, the theatre burned down. The diorama had been Daguerre's simply source of income. At kickoff glance, the event was tragically fateful. But the enterprise was already close to its end, thus losing the diorama tableaux was not completely disastrous, considering the funds granted under the insurance.

Portraits of and artworks by Louis Daguerre [edit]

-

Portrait by unknown lensman (circa 1844).[8]

-

Portrait by Charles Meade (1848).

-

Portrait by Due east. Thiésson (1844).

-

Portrait by Jean-Baptiste Sabatier-Absorb (1844).

-

See as well [edit]

- John Herschel

- Frederick Langenheim

- List of people considered father or female parent of a field

- Palladiotype

- Photographic processes

- Platinotype Visitor

- William Willis

- Daguerreotype

References [edit]

- ^ "The First Photograph — Heliography". Archived from the original on six October 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

from Helmut Gernsheim'south article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ... In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate ... The sunlight passing through ... This beginning permanent example ... was destroyed ... some years later.

- ^ Stokstad, Marilyn; David Cateforis; Stephen Addiss (2005). Art History (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Didactics. pp. 964–967. ISBN0-13-145527-3.

- ^ Daniel, Malcolm. "Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography". Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "January 2, 1839: Get-go Daguerreotype of the Moon". APS Physics. APS.

- ^ National Geographic, October 1989, pg. 530

- ^ "Daguerre". UC Santa Barbara Department of Geography . Retrieved eighteen November 2011.

- ^ "'A State Pension for L. J. M. Daguerre for the clandestine of his Daguerreotype technique' by R. Derek Wood". Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Wood, R.D., Annals of Science, 1997, Vol 54, pp. 489–506.

- ^ "Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre". The Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved 9 Apr 2021.

Sources [edit]

- Carl Edwin Lindgren. Teaching Photography in the Indian School. Photo Merchandise Directory: 1991. Bharat International Photographic Council. Edited: N. Sundarraj and One thousand. Ponnuswamy. VII IIPC-SIPATA Intl. Workshop and Conference on Photography — Madras, p. nine.

- R. Colson (ed.), Mémoires originaux des créateurs de la photographie. Nicéphore Niepce, Daguerre, Bayard, Talbot, Niepce de Saint-Victor, Poitevin, Paris 1898

- Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, Fifty.J.M. Daguerre. The History of the Diorama and the Daguerreotype, London 1956 (revised edition 1968)

- Beaumont Newhall, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Various Processes of the Daguerreotype and the Diorama by Daguerre, New York 1971

- Hans Rooseboom, What'southward incorrect with Daguerre? Reconsidering sometime and new views on the invention of photography, Nescio, Amsterdam, 2010 (www.nescioprivatepress.blogspot.com)

- Daguerre, Louis (1839). History and Practise of the Photogenic Drawing on the True Principles of the Daguerreotype with the New Method of Dioramic Painting. London: Stewart and Murray.

A practical description of that process called the daguerreotype.

- Daniel, Malcolm. "Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography." The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art – Dwelling. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011. Web. 17 January 2012.

- Gale, Thomas. "Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre." BookRags. BookRags, Inc., 2012. Web. 14 April 2012.

- Kahane, Henry. Comparative Literature Studies. 3rd ed. Vol. 12. Penn Country Upward, 1975. Print.

- Maggi, Angelo. "Roslin Chapel in Gandy'southward Sketchbook and Daguerre's Diorama." Architectural History. 1991 ed. Vol. 42. SAHGB Publications Limited, 1991. Print.

- Szalczer, Eszter. "Nature'due south Dream Play: Modes of Vision and August Strindberg's Re-Definition Of the Theatre." Theatre Journal. 1st ed. Vol. 53. Johns Hopkins UP, 2001..Impress.

- "Classics of Science: The Daguerreotype." The Scientific discipline News-Letter. 374th ed. Vol. 13. Club For Scientific discipline & the Public, 1928. Print.

- Watson, Bruce, "Light: A Radiant History from Creation to the Quantum Age," (London and NY: Bloomsbury, 2016). Print.

- Wilkinson, Lynn R. "Le Cousin Pons and the Invention of Ideology." PMLA. 2nd ed. Vol. 107. Mod Language Association, 1992. Print.

- Wood, R. Derek. "The Diorama in Great Britain in the 1820s". Annals of Science, Sept 1997, Vol 54, No.v, pp. 489–506 (Taylor & Francis Group). Web.(Midley History of early on Photography) fourteen April 2012

External links [edit]

- Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- DIORAMAS

- Louis Daguerre and Bry-sur-Marne

- Louis Daguerre Biography

- Louis Daguerre (1787–1851) from Globe Broad Art Resource.

- Daguerre, Louis Jacques Mande by Robert Leggat.

- Daguerre and the daguerreotype An array of source texts from the Daguerreian Society web site

- Daguerre'south Boulevard du Temple photo – a discussion on its making and subsequent history.

- Daguerre Memorial in Washington D.C.

- Louis Daguerre Encyclopædia Britannica

- Daguerre in a historical context

- [1]

- Official Website of Bry-Sur-Marne'due south Museum - Enhancement of the museum'due south collections, some are related with the work of Louis Daguerre.

- [two] - Rediscovery past Dutch lensman Wilmar explaining the shutterspeed of the Boulevard du Temple photograph.

- Works by Louis Daguerre at Project Gutenberg

- Works past or virtually Louis Daguerre at Internet Archive

0 Response to "How Did Louis Daguerre Contribution to Photography"

Post a Comment